Sections

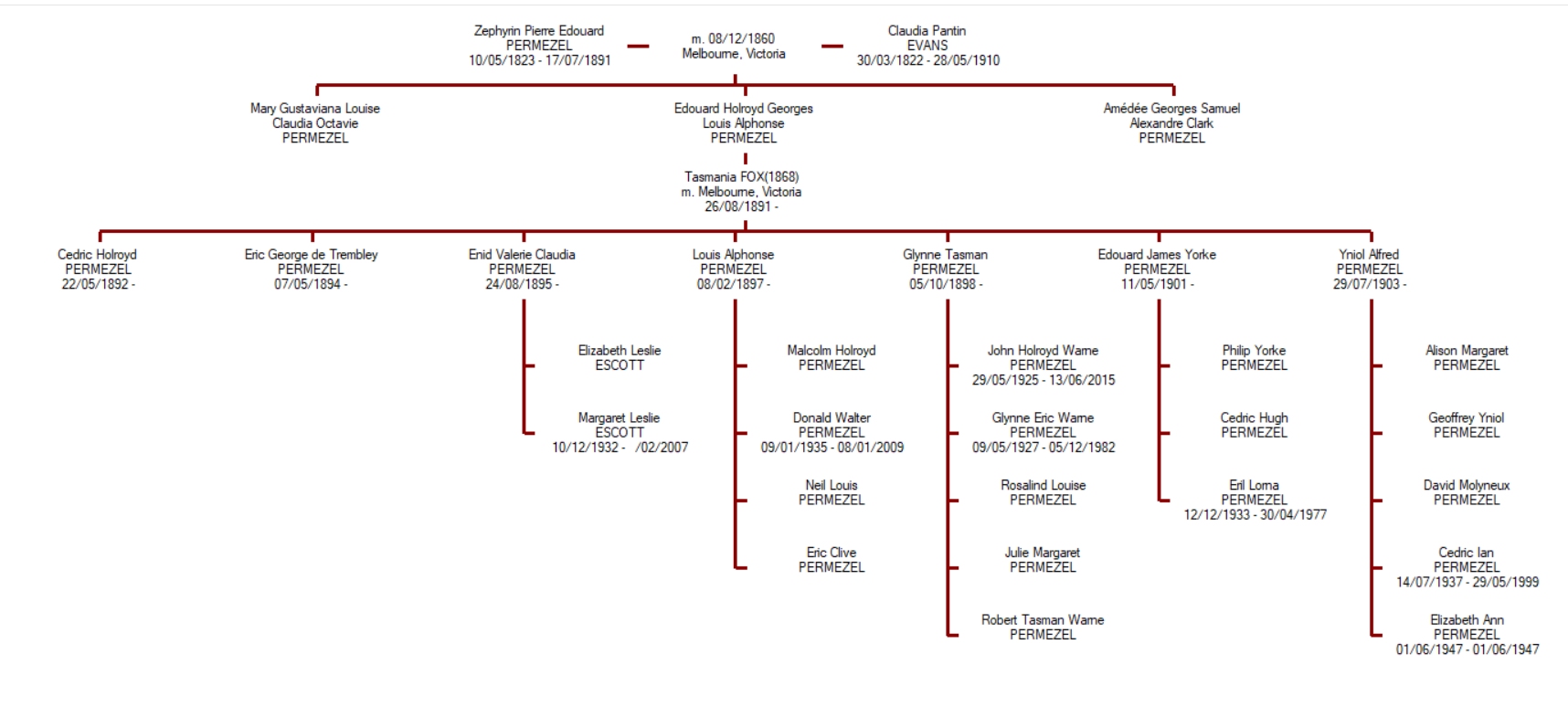

- Zephirin and Claudia

- The Evans

- Alf and Tassie

- Amédée and Grace

- Letters

1. Zephirin and Claudia

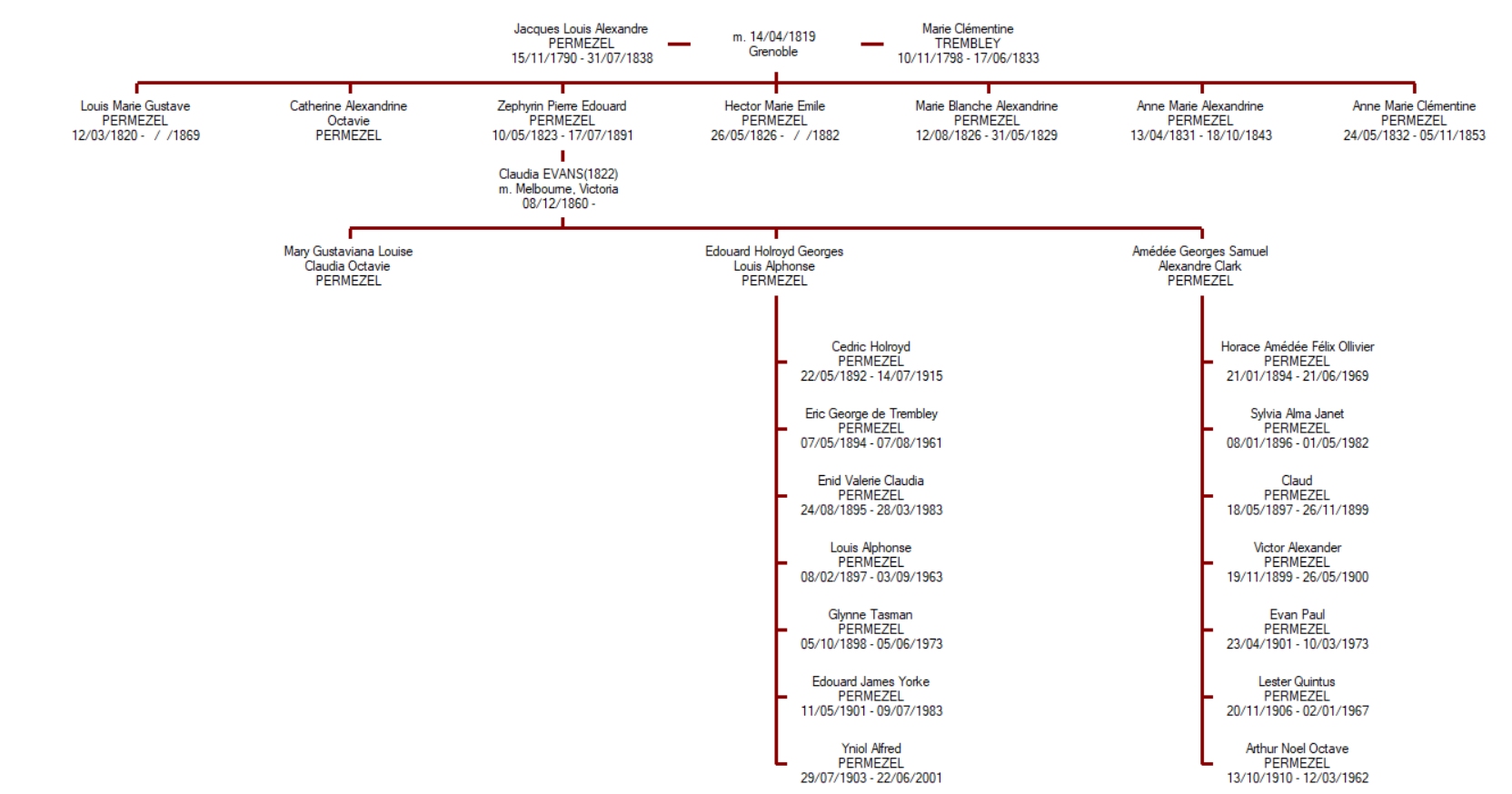

Edouard((1823) was 10 years old when his mother died in 1833 and still a minor when his father died in 1838. Along with his younger brother Emile (1826) and sisters Alexandrine (1831) and Clémentine (1832), M. Léon Silvy (1) brought up Edouard. Edouard’s aunt Anne-Laure Trembley married Hector Gayme and Hector’s sister Aimée had married Celestin, the son of M. Leon Silvy. The orphans were now living in Grenoble where Edouard attended the private school of the MM. Tioller. Later he attended the Royal Academy in Chambéry and his education was completed at the Lycée of Grenoble. He graduated with a Diplôme de Bachelor ès Lettres in 1842 (2) and then studied law, graduating in 1845 with a Licentiate en Droit.

Edouard((1823) was 10 years old when his mother died in 1833 and still a minor when his father died in 1838. Along with his younger brother Emile (1826) and sisters Alexandrine (1831) and Clémentine (1832), M. Léon Silvy (1) brought up Edouard. Edouard’s aunt Anne-Laure Trembley married Hector Gayme and Hector’s sister Aimée had married Celestin, the son of M. Leon Silvy. The orphans were now living in Grenoble where Edouard attended the private school of the MM. Tioller. Later he attended the Royal Academy in Chambéry and his education was completed at the Lycée of Grenoble. He graduated with a Diplôme de Bachelor ès Lettres in 1842 (2) and then studied law, graduating in 1845 with a Licentiate en Droit.

Shortly afterwards, Edouard appears to have started his travels (3). This had been made possible from the inheritances he had received, principally from his respective grandfathers. He is known to have visited England around 1850. It is known that he was in Mostaganem, Algeria in early 1852 where he was fined, by a police magistrate, the sum of 50 francs for a hunting misdemeanor. His occupation was given as an ‘entrepreneur de genie’ which probably was some form of contractor. This enterprise does not seem to have been a success and Edouard lost money, most probably due to failure of the local authorities to pay for services. Edouard apparently did not keep his brothers and sisters informed of his whereabouts, although the family solicitor (M. Pegoud) apparently did know, but was sworn to secrecy. At one stage, Edouard appears to have indicated to M. Pegoud that he intended to go to America, where his cousin Dominique Michoud had a slave plantation. When his family could not locate Edouard in the early 1850’s, it was therefore assumed that he had gone to America. Next he was reported to be in Paris incognito. The family were getting fed up with the disappearance of Edouard (4). The reality was that he had gone to Australia, presumably to replenish the fortune he had lost in his activities in Algeria, on the goldfields.

Shortly afterwards, Edouard appears to have started his travels (3). This had been made possible from the inheritances he had received, principally from his respective grandfathers. He is known to have visited England around 1850. It is known that he was in Mostaganem, Algeria in early 1852 where he was fined, by a police magistrate, the sum of 50 francs for a hunting misdemeanor. His occupation was given as an ‘entrepreneur de genie’ which probably was some form of contractor. This enterprise does not seem to have been a success and Edouard lost money, most probably due to failure of the local authorities to pay for services. Edouard apparently did not keep his brothers and sisters informed of his whereabouts, although the family solicitor (M. Pegoud) apparently did know, but was sworn to secrecy. At one stage, Edouard appears to have indicated to M. Pegoud that he intended to go to America, where his cousin Dominique Michoud had a slave plantation. When his family could not locate Edouard in the early 1850’s, it was therefore assumed that he had gone to America. Next he was reported to be in Paris incognito. The family were getting fed up with the disappearance of Edouard (4). The reality was that he had gone to Australia, presumably to replenish the fortune he had lost in his activities in Algeria, on the goldfields.

In September 1852, Edouard boarded the ‘Sea Nymph’ bound for Port Philip (5) from London. The ship was chartered on ‘the mutual co-operation principle’ and it appears that all the passengers were English except four who were French. These latter joined the ship after the original passenger manifest had been completed. The manifest lists the French passengers as follows:- Permigel Edouard male 29 years French, -/- Amichoud female 32 years -/-, -/- Leone female 9 years -/-, -/- Pollie female less than 1 year -/-. While the surname is misspelt, there can be no doubt that this is Edouard, but who are his fellow French passengers? They were certainly travelling as a family (6). Were Edouard and Amichoud married? Were Leone and Pollie his children? The age of Leone would put her birth about 1843 when Edouard was studying law in Grenoble. Pollie would probably have been born while Edouard was in Algeria. On the other hand, Amichoud could have been his mistress and the children hers by another relationship. There is no other reference to them and it is intriguing that Edouard had omitted to inform his children by Claudia Evans of his earlier visit to Australia at all. A search of the early records of marriages or deaths in Victoria, New South Wales, Tasmania and Western Australia has failed to find a reference to Amichoud, Leone or Pollie.

The next positive information of Edouard’s whereabouts is contained in a letter to his elder sister Catherine(1821), written from Sandhurst-Town (now Bendigo) on 14 April 1855 (7). Edouard states that he had written to his elder brother Gustave on 1 January 1855 and that he was injured in the gold mines. In the letters, he tells of his success as a gold miner, having found 500 pound sterling of gold in nine months. Other letters were written to Gustave and to his brother-in-law Anthelme, the last being written on 1 March 1857 from Bendigo. At no time was there any reference to a wife or family.

Edouard returned to Europe about the middle of 1858, as Emile writes in a letter dated 31 July 1858 to Anthelme – that Edouard is in Paris and will soon be in Grenoble. After his return Edouard appears to have spent most of his time in Paris, but visited Grenoble and Pont de Beauvoisin. Sometime in 1858, he decided to return to Victoria and this decision was definite by early 1859 (9). In 1859 Edouard was living in Paris at 16 rue de Ponts au Choix and entered into a partnership with his elder brother Gustave(1820) with the objective of setting up a silk importing business “Permezel Bros.’ in Melbourne. He borrowed 445 livres from his brother to assist in establishing the business.

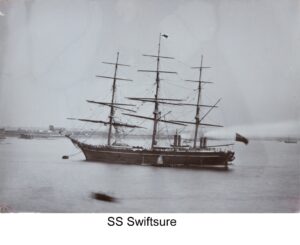

His passport (10), which was issued in Paris on 18 April 1859, describes him as 163 cm tall , having light auburn hair, although mainly bald, and brown eyes. Edouard left France a few days after his passport was issued – never to return. On the 3 May, he left London on the ‘SS Swiftsure’ for Melbourne via Plymouth.

, having light auburn hair, although mainly bald, and brown eyes. Edouard left France a few days after his passport was issued – never to return. On the 3 May, he left London on the ‘SS Swiftsure’ for Melbourne via Plymouth.

Edouard arrived in Melbourne in August 1859. His early address was 129 Collins Street (11) and it is assumed that this was his place of residence. Shortly afterwards, Permezel Bros was established at 37 Flinders Lane (12) which is between Spring and Exhibition Street. It apparently was not a success and the partnership was dissolved in 1862 (13) but it was many years before he had repaid the loans to his brother and to Gustave’s heir, his daughter Valentine(1843). One explanation given (14) was the long delay between the placement of the order in Melbourne and the subsequent delivery of the goods. This appears reasonable when it is considered that 100 days would be required to get the order to France, let alone procure the goods, arrange shipment and the actual transit to Melbourne.

Also on the voyage out to Australia were Claudia Pantin Evans (1822) and her sister Mary Pantin Evans (15). They were the sisters of the Honorable Dr George Samuel Evans, Postmaster-General in the Victorian Parliament. George had invited them to come to Melbourne and paid their fares (16). It is not known why he invited them, but perhaps it was because they were spinsters and Claudia appears to have been a favourite of George.

Also on the voyage out to Australia were Claudia Pantin Evans (1822) and her sister Mary Pantin Evans (15). They were the sisters of the Honorable Dr George Samuel Evans, Postmaster-General in the Victorian Parliament. George had invited them to come to Melbourne and paid their fares (16). It is not known why he invited them, but perhaps it was because they were spinsters and Claudia appears to have been a favourite of George.

The popular view (17) is that Edouard and Claudia met on the ship and formed an attachment that ultimately led to marriage. Charles Charretton says in a letter 14 October 1859, written after the receipt of a letter from Melbourne -‘You were able to meet your friend the English doctor and others that you knew from your previous trip’. George Evans was, in fact, a doctor of law and came to Melbourne in 1853, establishing himself as a barrister and solicitor. It is possible that he had previously met George Evans in Australia and that the romance really developed as a result of his earlier friendship with Claudia’s brother. Claudia had been, for sometime, governess in Rotterdam to the grandchildren of the British Consul there. Edouard had traveled and perchance had met her there. After all Edouard chose to sail from an English port rather than a European one. There is some credence to the possibility that he already knew her because in 1858 Alphonse in a letter (18) implies that Edouard will be marrying in Australia. Whatever the circumstances of their meeting, Edouard and Claudia were married at the Church of England and Ireland, South Yarra in Melbourne on 8 December 1860. The witnesses to the marriage (19) were Gurney Patmore, Edward Holroyd, Thomas Henry Pyke and Claudia’s sister Mary – all were passengers on the ‘Swiftsure’, and a John Wilson.

The popular view (17) is that Edouard and Claudia met on the ship and formed an attachment that ultimately led to marriage. Charles Charretton says in a letter 14 October 1859, written after the receipt of a letter from Melbourne -‘You were able to meet your friend the English doctor and others that you knew from your previous trip’. George Evans was, in fact, a doctor of law and came to Melbourne in 1853, establishing himself as a barrister and solicitor. It is possible that he had previously met George Evans in Australia and that the romance really developed as a result of his earlier friendship with Claudia’s brother. Claudia had been, for sometime, governess in Rotterdam to the grandchildren of the British Consul there. Edouard had traveled and perchance had met her there. After all Edouard chose to sail from an English port rather than a European one. There is some credence to the possibility that he already knew her because in 1858 Alphonse in a letter (18) implies that Edouard will be marrying in Australia. Whatever the circumstances of their meeting, Edouard and Claudia were married at the Church of England and Ireland, South Yarra in Melbourne on 8 December 1860. The witnesses to the marriage (19) were Gurney Patmore, Edward Holroyd, Thomas Henry Pyke and Claudia’s sister Mary – all were passengers on the ‘Swiftsure’, and a John Wilson.

Both Claudia and Mary Evans had been governesses and there are strong leanings in the Evans family towards education. Their father (Rev. George Evans) founded the Mile End School in London, the Hon. George had been earlier Headmaster of the Mill Hill School in Manchester, George’s brother Richard was possibly the Headmaster of the Rochester Classical and Mathematical School and another brother James had had a school before entering the legal profession. Edouard himself was well qualified academically.

The result was that the three established the Melbourne Ladies College for the daughters of gentlefolk in 1862. Whether this action precipitated the failure and dissolution of the partnership with Gustave or the latter was the catalyst for the establishment of the College is, as yet not known. The school was located at Talbot Lodge in Grey Street, East Melbourne near the corner of Powlett Street and had both day students and boarders. The pupils included the daughters of the establishment of the day – members of the judiciary and academia (20). As late as the mid 1940’s, there were women alive who had attended the school (21). The school continued at the East Melbourne site until 1877.

Edouard was granted a Bachelor of Arts degree at the University of Melbourne in 1865. Until 1865 there had been only 49 graduates of the University but it is not known whether the degree was awarded on the basis of examination or on recognition of his French qualifications. He was definitely a visiting professor of French at Wesley College in the late 1860’s (22). He taught at Wesley for many years probably until the late 1870’s. He also taught French at Scotch College about the same time.

During this time three children were born to Claudia – Octavie(1862), Edouard Alphonse(1864) and Amédée(1866). Claudia appears to have been the driving force behind the school and apparently did not relinquish this role with the advent of a family.

In 1868 Gustave died while Edouard still owed him 400 livres. Charles Charreton drew up a deposition (23) for repayment of the debt to Valentine(c.1845) at the rate of 5 livres per month through the Oriental Bank. There is very little correspondence surviving after that time between Edouard and his family in France.

Edouard took out a Miner’s Right (24) in 1863 and found gold on the Mornington Peninsula. It was the practice of the Victorian Government to offer a reward for the discovery of new gold deposits. Edouard made a claim for his discovery (25) but it was disallowed because of an earlier finding. It is known that he visited and stayed with some people by the name of Clark at Buttlejork (now known as The Gap) which is about 8 km from Sunbury. Edouard liked shooting and this may have been his recreation.

The family moved in the establishment set which is evidenced by invitations to Government House functions and their friends were such people as Mr Justice Holroyd who was godfather to Edouard Alphonse(1864). Amédée has Clark as one of his Christian names, which possibly indicates a close association with the family at Buttlejork, as Edouard had Holroyd as another of his names. The link however could be through Claudia’s brother Alfred, who married Emily Clark and her brother John might have been godfather to Amédée.

In 1878 the trio of Edouard, Claudia and Mary established the new school, the St Kilda Ladies College, in Fitzroy Street, St Kilda, where Octavie joined the staff. The school occupied one house out of three with an adjoining allotment, which provided the garden. The house has since been demolished but the two adjoining terraces were still standing in 1980. From these remaining houses an indication of the appearance and layout can be surmised. The house in Fitzroy Street had been called ‘La Rochelle’ which appears to have had some special significance for Edouard. It is said that he carefully removed all traces of the name when the family moved from Acland Street to Crimea Street in 1888. This is interesting as it probably indicates that he may have become a Huguenot at some earlier stage in his life and this would account for his marrying a Protestant. Edouard died there in July 1891 and was buried in the St Kilda Cemetery (26).

After the death of Edouard, Claudia, Mary and Octavie carried on the school until it was sold in 1895. They then moved to Duncraig Avenue, Malvern. James Evans, Claudia and Mary’s nephew, lent 1050 pounds to Edouard Alphonse(1864) with a property in Duncraig Avenue, Malvern as security. He later transferred the mortgage (27) to Claudia and Octavie. It appears that James lived for some time with his aunts and cousin. He also lived in South Australia. Mary died in 1903 and Claudia in 1910.

The only surviving evidence of correspondence with relatives in France, after the death of Gustave, is the regular acknowledgements by Valentine(c.1845) of the repayments of the loan. However, Clémentine(1841) daughter of Edouard’s elder sister Catherine(1821) did correspond with Octavie until her death and Elisabeth Chevalier, Clémentine’s daughter continued to correspond with Octavie until the latter’s death in 1930. Edouard outlived by a number of years all his brothers and sisters in France.

No French relatives ever visited Australia until 1993 when two sisters, Muriel and Dominique Tschudnowsky – descendants of Edouard’s sister Catherine, met a number of their cousins in Melbourne, Sydney and Adelaide.

Much earlier the family did have a number of visits from the Evans family, however, some of whom lived in New Zealand.

—–ooooo—–

Footnotes – Terra Australis

(1) The information on the life of Edouard, prior to 1859, has been provided by Bruno Grosse(1930), a descendant of Edouard’s elder sister.

(2) His degree is in the possession of Michael (1954).

(3) His great friend Alphonse Arragon, in a letter to Edouard written about 1857 says ‘you were right to go away 10 years ago and travel the world….’. He lived in Pont de Beauvoisin in 1857 and knew Edouard’s brothers and his brother-in- law, Anthelme Chevalier.

(4) Emile(Hector (1828)), in a letter to his sister Octavie (Catherine (1821)), writes in 1853: –

‘…..What is one to do about this business of always having to excuse him on the grounds of his youth – that he is only 20 years old as one has said many times before – to excuse oneself as well as him. I do not think I am being more than normally severe, when I say that, really, these things are driving me mad and cause me to lose my head every time I think about it. He must be mad or a complete egoist to treat his family like this. I excuse all Edouard’s misdemeanours but what I regret is this isolation in which he wishes to live, isolation which has already caused him to lose the opportunity of ever making a success of himself. One is not strong when one walks lone. A reasonable man would support him in ‘all that surrounds him’ in order to avoid a tragedy. Edouard never thinks of this. ….’

(5) This important information was discovered by Rodney (1935). The ‘Sea Nymph’ arrived in Melbourne on 11 January 1853.

(6) A passenger, Thomas Cowle, kept a diary of the voyage which is in the Macquarie Library in Sydney. The diary has been transcribed to typewritten format and there are transcription spelling errors. In the diary, there are a number of references to the French passengers:-

Nov. 9, Tuesday morning, 1852……….. ‘Got the ingredients(and took them to one of the passengers, “a lady”, wife of a Frenchman”) to make some pancakes. She made us a dozen and we ate them for dinner and tea, minus 2 which we gave away.’…….. Nov. 28…………… Afternoon………… ‘Had a good supper with the French people consisting of French dishes and duff.’………. Dec. 17, Friday morning, 1852………. ‘Got the Frenchman to rub my downy skin with chloride of lime which I got for my birth’ (should be berth)……. Dec. 31,…….. List of Passengers ………………………. Married people & children, Main Cabin …………….. Madm. & Monsre. Venziel, 1 (1 child) ………… Single Females in Main and After Cabin Main Cabin ………… Madmsle. Penziel …………… .

(7) This letter details the problems with his leg and the inadequacy of medical treatment on the goldfields.

(8) His friend Alphonse (Arragon) in a letter dated 30 October 1858 comments on Edouard’s decision to return to Australia.

(9) Letter dated 12 January 1859 from his brother-in-law Anthelme talks of his return to Australia.

(10) Passport in possession of John (1925).

(11) Early correspondence from France is addressed to this address. It was just east of Russell Street and the building no longer stands. The Hyatt Hotel now occupies the site.

(12) Melbourne Directories of 1862 show this address for Permezel Bros.

(13) Document in possession of John dated 20 May 1862.

(14) Family folklore.

(15) Passenger manifest of the ‘Swiftsure’.

(16) Letter to Mary, Claudia’s sister, dated 15 May 1858 from George making arrangements for them to come to Melbourne.

(17) Family folklore.

(18) Letter dated 9 February 1859.

(19) Marriage Certificate No.3510 of 1860. Also a note from T H Pyke dated 4 December 1860.

(20) Testimonials contained in the school prospectus are from the Chancellor of the University of Melbourne, Mr Justice Holroyd, et alia.

(21) The grandmother of Professor Morehouse who lectured John (1925) at the University of Melbourne went to the College and was alive in 1944.

(22) Wesley College prospectus for 1870.

(23) Document dated 21 August 1874.

(24) Original in possession of John (1925).

(25) ‘History of Gold Discovery in Victoria’.

(26) Grave in Independent Section C64.

(27) Document dated 6 May 1903.

—–ooooo—–

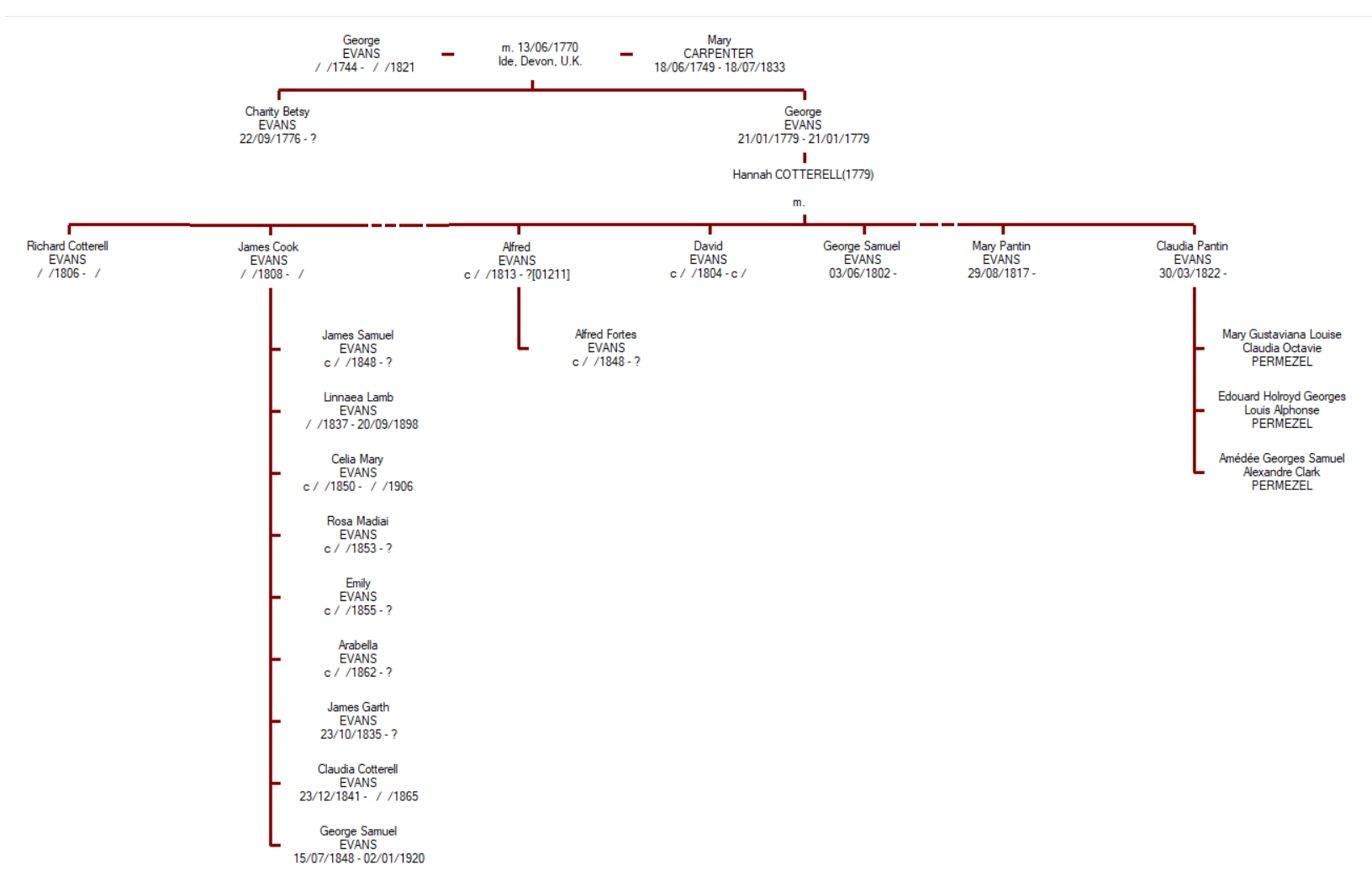

2. The Evans

The history of the Permezels in Australia would be incomplete if there were no mention of the other half of the common ancestry through Claudia Evans(1822), who married the founder of the Australian branch Zephirin Pierre Edouard. Claudia was the youngest daughter of the Reverend George Evans(1779) and Hannah Cotterall(1779).

The history of the Permezels in Australia would be incomplete if there were no mention of the other half of the common ancestry through Claudia Evans(1822), who married the founder of the Australian branch Zephirin Pierre Edouard. Claudia was the youngest daughter of the Reverend George Evans(1779) and Hannah Cotterall(1779).

On the Evans’ (1) side, George’s grandfather was also called George and was a parish clerk and wheelwright in Cadbury, Somerset. (Cadbury in Arthurian legend, was a possible site of Camelot and there is a mound there which is believed to be at least a fortification of King Arthur). George married a girl whose maiden name was Furze (or Fust) who had a twin sister who married a man called Pugh.

The only issue of this union was George Evans (1744) for Miss Furze died in childbirth and the father was killed a fortnight later. The son was brought up by his grandmother, Madame Furze, who ‘kept the Cadbury Crop’. What the `Cadbury Crop’ was is not known (2), but it was said to be `good for man and os’ – so is possibly an inn. Young George had been left some houses but these were destroyed by fire while he was still a minor.

George Evans (1744) married Mary Carpenter (1750), the daughter of Thomas Carpenter (1719-1799). They had at least one son, also called George, born on 21 January 1779 and who became Claudia’s father. Nothing is known of the early life of George (1779) but in 1801 he was ordained a priest and came under the influence of the Countess of Huntingdon, Walcott Vineyard, Bath. As such, George became one of the first ministers of the Congregational Church. He was a prolific preacher (3) and held the record for delivering more sermons than any other minister in England. He toured the length and breadth of the land to deliver his sermons.

His last parish was the Brunswick Chapel in Mile End, London, where he established a school for boys. The Chapel was destroyed during the Second World War but the almshouse next door survived. George died on 20 September 1846.

George (1779) married Hannah Cotterall (1779) on 2 July 1801. Hannah was the daughter of Richard Lewis Cotterall (1746) and Mary Morrison (1752). Richard was probably an attorney(or lawyer) for he worked in the office of his maternal grandfather – William Lewis, who was an attorney and lawyer. William Lewis had at least two daughters, Mary (1713) – the mother of Richard Cotterall, and Hannah, who died a spinster. The two Lewis girls inherited some property in Aberystwyth, Wales, so it is probable that the Lewis family came from there.

Mary Lewis married John Cotterall (1716) who was the Master, and part owner, of a ship that traded between Bristol and the West Indies. John Cotterall came from Liverpool and was drowned when his ship foundered with all hands in the Portland Roads, near Weymouth, sometime between 1746 and 1756. After the death of her husband, her father William Lewis placed Mary in the almshouse at Deptford (Trinity). The Trinity Almshouse was for old seamen and their widows. Captain James Cook was, at one time, superintendent of this establishment.

Mary and John had two sons, John and Richard. John Lewis Cotterall was born in 1744 and worked in customs. He is said to have died an old man in Liverpool. Richard Lewis Cotterall was born on 29 January 1746 and died 29 February 1828. He married, on 22 February 1772, Mary Morrison (1752).

Mary Morrison had two brothers, William and John (1760) and was the daughter of William Morrison and Mary Parsons. Her father was a Colonel in the Artillery at Woolwich and her paternal grandfather had been Postmaster-General in Dublin at the beginning of the eighteenth century. Colonel Morrison died in 1760. Mary’s mother was the daughter of a man called Parsons who was a pump and block maker in Wapping. Her mother’s maiden name was Mildning. Parsons, after the death of Mary’s mother, appears to have married Hannah Pantin (4), a widow of a man called Sibot.

It is probable that Mary’s mother died when she was quite young and she was brought up by her step-mother. There is evidence of a strong relationship with her step-sister, Hannah Sibot (5) who married William Abedward. Mary was to name her daughter Hannah after her step-sister. The name Pantin was also to become a christian name for all Mary’s granddaughters.

George Evans (1779) and Hannah Cotterall (1779) had five sons and three daughters, of whom Claudia (1822) was the youngest. They were George Samuel (1802), Richard Cotterall (1806), James Cook, William, Alfred, Hannah Pantin (1815), Mary Pantin (1817) and Claudia Pantin (1822). At least George and Richard are known to have been educated at the Merchant Tailors’ School, London, and it is probable that all the boys were educated there. Little is known of William who was said to be sickly.

The greatest amount is known of George (1802). After leaving school, he won a scholarship to St. John’s College, Oxford but for `family reasons’ (6) apparently left and went to Glasgow University, where he graduated with a Bachelor of Arts then Master of Arts. He was later to be admitted to the degree of Doctor of Civil and Canon Law. His first position was that of Headmaster of Mill Hill Grammar School, near London.

Shortly afterwards he sought appointment as Professor of Greek at London University but was not successful. About 1830, George moved a school that had been established at Kilburn, to North End House, Hampstead. From the prospectus, the school appears to have been very progressive for the time. On the staff were his brother Richard and Mrs. Riddiford, the Matron. George was later to marry Mrs. Riddiford (Harriet Strother). They were probably married before 1836, as George, his wife and her daughter Miss Riddiford (Amelia) traveled to Paris in 1836 (7).According to his passport, George was six feet (1.8m) tall, blond with light brown eyes.

Shortly afterwards he sought appointment as Professor of Greek at London University but was not successful. About 1830, George moved a school that had been established at Kilburn, to North End House, Hampstead. From the prospectus, the school appears to have been very progressive for the time. On the staff were his brother Richard and Mrs. Riddiford, the Matron. George was later to marry Mrs. Riddiford (Harriet Strother). They were probably married before 1836, as George, his wife and her daughter Miss Riddiford (Amelia) traveled to Paris in 1836 (7).According to his passport, George was six feet (1.8m) tall, blond with light brown eyes.

George gave up education as a career and was called to the bar at Lincoln’s Inn in 1837. About this time, the project of colonising New Zealand was under way and the New Zealand Association was formed with George as the Honorary Secretary. The actual organisation that established the settlement at Wellington was the New Zealand Land Company, of which George was appointed Principal Agent. He sailed with the first fleet on the `Adelaide”, arriving at Port Nicholson 7 March 1840. He has been referred to as the ‘father’ of Wellington, for it was largely through his oratorical powers that the City was located on its present site.

As the company representative, George brought with him a house, which he subsequently sold, to a whaler called Barrett, who converted it to a hotel. George was called upon to act on behalf of the settlers with the colonial administration and, no doubt, his legal vocation stood him in good stead. His step-daughter Amelia married, on 29 June 1842, Captain Edward Daniel Chetham, the son of Sir Edward Chetham. After three years in New Zealand, George returned to England and once again resumed legal practice in Lincoln’s Inn, where he was joined for some time by his brother, James Cook Evans.

George sought appointment as Judge of the Court of Requests for the Tower Hamlets but was unsuccessful. In 1852 he returned to New Zealand on a ship called `The Stag’, probably to dispose of some of the properties he had purchased in Wellington on his first voyage, which comprised about 44 one acre allotments. He did not stay long, for in the next year he appears as resident of 33 Flinders Lane, Melbourne (8). In 1854-55, his occupation is shown as a merchant at 34 Collins Street West. He again returned to the law in 1856, practising as barrister at 22 Temple Court.

He was a political writer for the Melbourne Herald for a number of years and its editor from 1855-58. In 1856 he was elected as member for Richmond (9) in the newly created Legislative Assembly. He played a large part in the defeat of the first O’Shanassy Ministry but was appointed the Postmaster-General in the second O’Shanassy Ministry. He lost his Richmond seat in 1859 but was elected, a short time later, as member for Maryborough and was again appointed to his old portfolio of Postmaster-General and Minister for Leases in addition.

George in a letter (10) to Henry Parkes (later Sir Henry) in 1856 proposed a federation of the Australian States and a Senate much along the lines of the current Senate.

His wife Harriet died on 31 March 1866 and George on 23 September 1868, in New Zealand. George’s brother Richard spent years at Wymondley House (theological college) and taught at North End House. He applied to become Headmaster, and probably did so, of the Chatham and Rochester Classical and Mathematical School.

James Cook Evans was a Latin and Greek scholar (11) and ran a boy’s school. His first wife, Linnaea Lamb, the daughter of Dr Lamb who was Medical Surgeon at Waterloo, operated a school for girls. Linnaea and their son James died and James gave up the school and read  for the law. Their only daughter, also Linnaea, was to emigrate to New Zealand, where she died in 1896. The `Times’ paid James 500 pounds a year as a reporter in the law courts. His second wife was Celia Shaw, who had taught at Linnaea’s girl’s school in the early days of his first marriage.

for the law. Their only daughter, also Linnaea, was to emigrate to New Zealand, where she died in 1896. The `Times’ paid James 500 pounds a year as a reporter in the law courts. His second wife was Celia Shaw, who had taught at Linnaea’s girl’s school in the early days of his first marriage.

James and Celia had seven children, two boys and five girls. The boys were George Samuel Evans (1848) and James Samuel Evans. Only three of the girls names are known, namely, Claudia who was born 23 December 1841 and named after her aunt Claudia Pantin Evans (1822), Rosey and Emily. Two of the girls were educated in France for a year and another in Germany. James became a barrister-in-law at Lincoln’s Inn and Secretary of the South Western Railway Company. He was very tall (6 feet 3 inches) and an accomplished water colour painter. He died in his sixtieth year after suffering paralysis, brought on by a disappointment of office and an accident on the railway.

Two of their sons, James and George, visited their aunts Claudia (1822) and Mary in Melbourne. George also lived in New Zealand with his half-sister Linnaea, but was later to settle in South Australia, where he died in 1920.

James was the principle beneficiary under the Will of his uncle George Samuel(1802) and income from the estate was still being paid to James’ widow (Amy Farren) until the late 1930’s. It was a condition of the will that James should spend some time each year in New Zealand but as far as is known he never visited the country.

Another brother Alfred was a medical practitioner and married, on 19 February 1846, Emily Clark (1824). They had at least one son, Alfred Fortes who married Florence Georgina Murrows on 20 May 1873. Alfred and Florence had six children – Emily (1874), Grace (1875), Alfred (1878), Marjorie (1879), Dinah (1881) and George (1883). Florence corresponded with Octavie (1862) during their lifetimes. Cedric (1892), Eric (1894) and Glynne (1989) Permezel visited members of the family during the First World War. Elizabeth Escott (1928), the daughter of Enid (1895), also visited the family in the 1950’s. Alfred visited Russia in 1834, most probably St. Petersburg, and, on the voyage home in September, copied a manuscript of Opus 12 of Edouard Wenzel for his sister Mary.

Another brother Alfred was a medical practitioner and married, on 19 February 1846, Emily Clark (1824). They had at least one son, Alfred Fortes who married Florence Georgina Murrows on 20 May 1873. Alfred and Florence had six children – Emily (1874), Grace (1875), Alfred (1878), Marjorie (1879), Dinah (1881) and George (1883). Florence corresponded with Octavie (1862) during their lifetimes. Cedric (1892), Eric (1894) and Glynne (1989) Permezel visited members of the family during the First World War. Elizabeth Escott (1928), the daughter of Enid (1895), also visited the family in the 1950’s. Alfred visited Russia in 1834, most probably St. Petersburg, and, on the voyage home in September, copied a manuscript of Opus 12 of Edouard Wenzel for his sister Mary.

—–ooooo—–

Footnotes – The Evans

(1) Based largely on notes which may have been prepared by George Evans(1802).

(2) Enquires by John(1925), including at Cadbury itself in 1987 have failed to positively identify the nature of the `Crop’.

(3) History of the Congregational Church.

(4) Letters of Administration for estate of Michael Pantin, brother of Hannah.

(5) Marriage certificate of Richard Cotterall and Mary Morrison. William Abedward and his son were witnesses to the wedding.

(6) A profile of George(1802) published in the Melbourne Leader, 5 April 1862.

(7) Passport of George(1802).

(8) Victorian Directories.

(9) Ibid. (6).

(10) Letter dated 30 June 1856 in Mitchell Library.

(11) Based on notes prepared by one of his son’s, probably by James Samuel.

3. Alf and Tassie

Edouard (1864) was known to his parents as Alphonse and to others as Alf. He was educated at Scotch College when it wa

Edouard (1864) was known to his parents as Alphonse and to others as Alf. He was educated at Scotch College when it wa s located at the east of Melbourne, near where St Andrews Hospital is today. This would, of course, be quite near where his parents had their school in East Melbourne. After leaving school, he attended the University of Melbourne where he studied law.

s located at the east of Melbourne, near where St Andrews Hospital is today. This would, of course, be quite near where his parents had their school in East Melbourne. After leaving school, he attended the University of Melbourne where he studied law.

As a young man he was very active and, in his mother’s eyes, quite daring, and she, at least on one occasion, found it necessary to admonish him on this account. He liked sport and, at one time during the 1890’s, he played for the St. Kilda Football Club (1) – although the club does not currently recognise this.

By 1990 he had established himself as a solicitor with a practice at 99 Queens Street in the name of Hughes and Permezel. Whether Hughes was in the practice in the early days is not known but Alf certainly was the principal in later years. His law practice was not confined to Melbourne and he regularly visited the country where his firm is known to have had branches in Romsey and as far afield as Bright. There exists a photograph (2) taken on market day in Romsey in 1910 of a group of men outside the hotel and Alf is among them. The practice acted for a number of hotels, which represented a sizeable proportion. The practice was later to move to 491 Chancery  Lane (now Little Collins Street).

Lane (now Little Collins Street).

Alf married Tasmania Mary Johanna Fox (1868), the daughter of Mary Emily McPherson (1839) and William Fox (1830).

Mary was the daughter of Captain Daniel James McPherson (1805) and Frances Anne Boore (1812). Daniel  McPherson was born in London and is believed to be the son of a Royal Naval Officer. It has been claimed that his father, also Daniel, served on Admiral Nelson’s flagship, the `Victory’, under Captain Hardy at Trafalgar (3) but there is no Daniel McPherson listed as serving in Battle of Trafalgar. Daniel went to sea at an early age and captained a number of ships before settling in Australia in the beginning of the 1840’s. His wife Frances followed him arriving in December 1842 with their family of three

McPherson was born in London and is believed to be the son of a Royal Naval Officer. It has been claimed that his father, also Daniel, served on Admiral Nelson’s flagship, the `Victory’, under Captain Hardy at Trafalgar (3) but there is no Daniel McPherson listed as serving in Battle of Trafalgar. Daniel went to sea at an early age and captained a number of ships before settling in Australia in the beginning of the 1840’s. His wife Frances followed him arriving in December 1842 with their family of three  girls of whom Mary was the youngest. By 1845, they were living in Williamstown and Daniel was a pilot. Later he was to be asked by Governor La Trobe to be the Harbour Master for the Port of Geelong and he took up the appointment in 1856 and remained there until 1865. Daniel’s wife Frances came from Sutton Benger, Wiltshire, and her father Richard Boore is quite a mystery man for, apart from his listing as her father, and that of her siblings, there is no other record at all.

girls of whom Mary was the youngest. By 1845, they were living in Williamstown and Daniel was a pilot. Later he was to be asked by Governor La Trobe to be the Harbour Master for the Port of Geelong and he took up the appointment in 1856 and remained there until 1865. Daniel’s wife Frances came from Sutton Benger, Wiltshire, and her father Richard Boore is quite a mystery man for, apart from his listing as her father, and that of her siblings, there is no other record at all.

William Fox married Mary McPherson in Geelong at All Saints Church on 9 February 1864. William was born in Salzpittern (4), which is near Hannover, West Germany. His original German name was Georg Frederich Christian Wilhelm Fuchs and was the son of Georg Fuchs and Johanna Schaefer. His father was the Master of the salt works, presumably at Salzpittern. When and why William came to Australia is not known but it could have been as a result of the Berlin uprisings, which caused many Germans to migrate. Anyway by 1864 he had anglicised his name to Fox and described himself as a merchant.

Tassie was born at `Liebenhalle’, Robe Street, St. Kilda on 1 October 1868 and lived there until she married Alf on 26 August 1891. Robe Street intersects with Acland Street where the Permezel school was located after 1878. Tassie was one of the early pupils at the Presbyterian Ladies College but she may have attended the Permezel school beforehand. In any case, the two families would have known each other as near neighbours.

At the time of their marriage, Alf settled in trust for Tassie the sum of 1000 pounds (5). The trustees were Tassie’s two brothers: Melbourne, then a law student, and Sydney, a clerk. Melbourne was later to join Hughes and Permezel as a solicitor and, after the death of Alf, to purchase the firm.

Their first home was in Durham Street, Hawthorn but before the end of the century, they moved to “Voreppe”, Jessie Street (now Forster Avenue), East Malvern, which would remain the family home until Alf’s death in 1919.

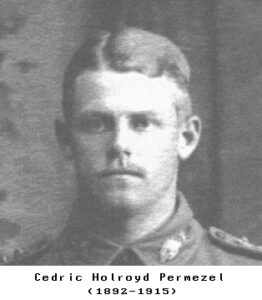

Alf and Tassie had seven children – Cedric (1892), Eric (1894), Enid (1895), Louis (1897), Glynne (1898), Edouard (1901) a nd Yniol (1903). The eldest, Cedric, attended Malvern Grammar School and completed his education at Scotch College. After he left school he joined Dalgety’s. During this period prior to the First World War, Cedric was active with the Essendon Rifles where he rose to the rank of Lieutenant. On the declaration of war in 1914, Cedric enlisted the same day and later that year left for Europe. After some time in England, he became part of the Australian and New Zealand Expeditionary Force training in Egypt. Cedric was now a Captain in the 7th Battalion. He took part in the Gallipoli campaign where he was fatally wounded and died on board the hospital ship two days later(14 July 1915).

nd Yniol (1903). The eldest, Cedric, attended Malvern Grammar School and completed his education at Scotch College. After he left school he joined Dalgety’s. During this period prior to the First World War, Cedric was active with the Essendon Rifles where he rose to the rank of Lieutenant. On the declaration of war in 1914, Cedric enlisted the same day and later that year left for Europe. After some time in England, he became part of the Australian and New Zealand Expeditionary Force training in Egypt. Cedric was now a Captain in the 7th Battalion. He took part in the Gallipoli campaign where he was fatally wounded and died on board the hospital ship two days later(14 July 1915).

Alf was devastated by the death of his eldest son and threw himself into the war effort, particularly in helping those who had suffered losses like his own. He did this at the expense of his legal practice, which suffered as a result. Consequently, when he died there was little provision for Tassie and the other boys had to rally round and help to support their mother.

The legal practice was sold to Tassie’s two brothers, Sydney and Melbourne Fox, but it was many years before the full proceeds of the sale were recovered. It became the responsibility of Alf’s son Glynne (1898), himself a law student, to act on behalf of his mother in the negotiations with his uncles. Final settlement of the sale did not occur until after the death of Tassie in 1924.

The other sons also started school at Malvern Grammar School, which was then located in Coppin Street, East Malvern. However, after a few years at Malvern they completed their education at Wesley College in Punt Road, Prahran. In the early 1900’s an electric tram started operating from the corner of Burke and Wattletree Roads, East Malvern and went to the St Kilda Junction. It was a short walk up Punt Road to Wesley. This apparently was considered to be more convenient than travelling to the city on the steam train fro m Darling Station. The boys rode a horse from Jessie Street to the tram terminus.

m Darling Station. The boys rode a horse from Jessie Street to the tram terminus.

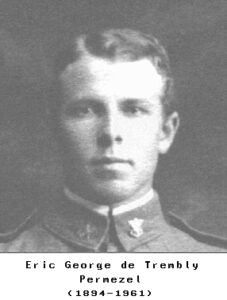

The second son, Eric (1894), enlisted in November 1914 and rose to the rank of Captain in the 5th Battalion. He received the Military Cross (6) for his actions at St Martin Wood on 23 August 1918.

Louis (1897) also tried to enlist but was rejected on medical grounds. Alf and Tassie’s only other son of military age, Glynne (1898) did enlist and was sent to France as a gunner reinforcement for the 103rd Howitzer Battery. However, by the time he was due to go to the front line, the war was over. On the way to the front, Glynne heard Eric’s voice in the dark – Eric was on his way back and was going home to Australia (7).

—–ooooo—–

Footnotes – Alf and Tassie

(1) Edouard Yorke (1901) told John (1925) that Alf captained the club but this has not been substantiated.

(2) Melbourne `AGE’ 12 April 1980. Alf is the 5th from the left in a black hat.

(3) Letter from Anna Quinton to Alice Moggs of unknown date.

(4) Shown on marriage certificate.

(5) Settlement date 24 August 1891.

(6) Eric’s Military Cross is in the possession of Malcolm(1933).

(7) See Appendix 21

4. Amédée and Grace

[by Paul Permezel(1925)]

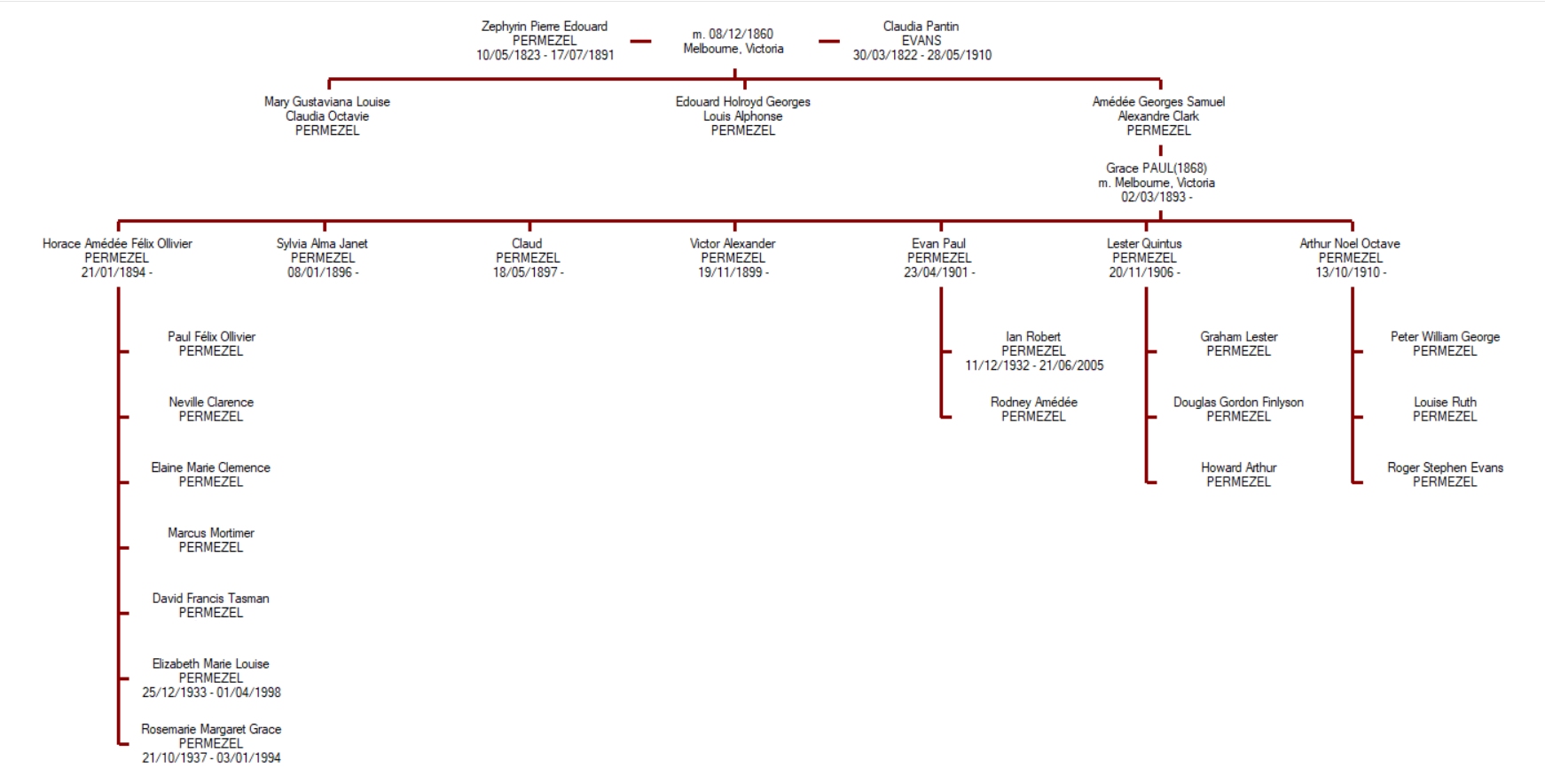

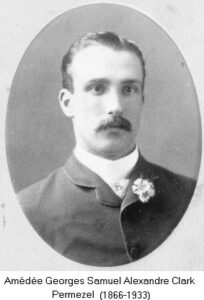

Amédée Georges Samuel Alexandre Clark Permezel was born at East Melbourne on 31-12-1866. He was the youngest of the three children of Edouard Permezel and his wife Claudia (née Evans). The other two children were Mary Gustaviana Louise Claudia Octavie (1863-1930), and Edouard Holroyd Georges Louis Alphonse (1864-1919).

Amédée Georges Samuel Alexandre Clark Permezel was born at East Melbourne on 31-12-1866. He was the youngest of the three children of Edouard Permezel and his wife Claudia (née Evans). The other two children were Mary Gustaviana Louise Claudia Octavie (1863-1930), and Edouard Holroyd Georges Louis Alphonse (1864-1919).

Amédée Permezel passed his final examination for a Bachelor of Law degree at Melbourne University in November 1892 in the company of five other male candidates.

Amédée Permezel passed his final examination for a Bachelor of Law degree at Melbourne University in November 1892 in the company of five other male candidates.

In 1893 Amédée married Grace Clementine Paul, who with her twin brother John Colin, was born at St. Kilda in 1868. Grace Clementine’s father, the Reverend Arthur Paul, arrived in New South Wales in November 1853 from Scotland. He came to Melbourne in November 1854, and married Janet Brown Moffat in 1859. All their twelve children were born at the Manse of the Free Presbyterian Church in Alma Road St. Kilda. Arthur Paul died at the age of 84 at the Manse in 1910 after having served as the minister of the Free Presbyterian Church, St. Kilda for 55 years.

Amédée practised law in Melbourne, Bacchus Marsh, and Yarrawonga.

Seven children were born to Amédée and Grace Permezel. Two children died at an early age (212, 6mths). The five surviving children were: Horace Amédée Ollivier (1894-1969), Sylvia Alma Janet (1896-1982), Evan Paul (1901-1973), Lester Quintus (1906-1967) and Arthur Noel Octave (1910-1962). Horace was born at St. Kilda – Sylvia, Lester and Evan Paul were born at Bacchus Marsh; and Arthur was born at Yarrawonga.

Seven children were born to Amédée and Grace Permezel. Two children died at an early age (212, 6mths). The five surviving children were: Horace Amédée Ollivier (1894-1969), Sylvia Alma Janet (1896-1982), Evan Paul (1901-1973), Lester Quintus (1906-1967) and Arthur Noel Octave (1910-1962). Horace was born at St. Kilda – Sylvia, Lester and Evan Paul were born at Bacchus Marsh; and Arthur was born at Yarrawonga.

Amédée moved with his family from Bacchus Marsh to Yarrawonga in 1907. Although Amédée was a commendable student at Wesley(1883), and subsequently completed an articled clerkship rising to a law degree at Melbourne University (1892), his law practices were not particularly remunerative. His five children were largely educated at state schools, although Horace had a 2-year stint at a small private school at Yarrawonga (Alexandra College?), and Arthur attended All Saints Grammar School in St.Kilda. Lester obtained a Bachelor of Law degree at Melbourne University. Horace studied banking and accountancy by correspondence via Hemingway & Robertson.

At this writing, there is no record of when Amédée and family moved back to Melbourne, although from family photographs and letters, it is known that the family still resided at Yarrawonga in 1916.

Horace was keenly aware of his eligibility for war service during the First World War. His cousin Cedric (1892-1915) and uncle Lester Laurie Paul (1881-1957) served in the AIF; Cedric died at Gallipoli. Horace was rejected at three separate attempts to enlist because of a foot deformity. Horace successfully applied to the Commercial Bank of Australia Ltd in 1909 for a position as a bank clerk. He had positions as a junior clerk, ledger keeper, and teller in CBA branches at St.Kilda and Williamstown, then as a clerical assistant to the general manager at head office, 333 Collins St. Melbourne.

Horace was keenly aware of his eligibility for war service during the First World War. His cousin Cedric (1892-1915) and uncle Lester Laurie Paul (1881-1957) served in the AIF; Cedric died at Gallipoli. Horace was rejected at three separate attempts to enlist because of a foot deformity. Horace successfully applied to the Commercial Bank of Australia Ltd in 1909 for a position as a bank clerk. He had positions as a junior clerk, ledger keeper, and teller in CBA branches at St.Kilda and Williamstown, then as a clerical assistant to the general manager at head office, 333 Collins St. Melbourne.

Around 1920, Horace was posted to his first position as a branch manager to Heywood, Vic. It was here that he met Ivy Rosina Ainsworth (1894-1975), a school teacher whom he married in 1922, by which time he had been transferred to manage the CBA branch at Jeparit, Victoria. (Robert Gordon Menzies was born at the back of his father’s general store in Jeparit in December 1894.)

Four of the seven children born to Horace and Ivy Permezel were born at Jeparit: Paul Felix Ollivier 20-02-1925, Neville Clarence 04-04-1926, Elaine Marie Clemence 25-02-1928 and Marcus Mortimer 24-06-1929. In June 1930, Horace was transferred to manage the CBA branch at Scottsdale, Tasmania. It was here that the remaining three children were born: David Francis Tasman 24-05-1932, Elizabeth Marie Louise (25/12/1933 – 01/04/1998) and Rosemarie Margaret Grace (21/10/1937 – 03/01/1994).

In January 1940, Horace was transferred to manage the CBA branch at Queenstown, Tasmania at which time the Mount Lyell Mining & Railway Co. Ltd was moving into its peak production period as Australia’s top producer of refined copper for industrial goods and munitions for the war effort.

Horace’s last and final posting was to Brighton (Adelaide) South Australia. in 1950, by which time Paul, Neville and David had already left home for the mainland. Soon afterwards, Marcus moved to Melbourne to continue and complete his civil engineering studies. Elaine, and Elizabeth while essentially still based at home in Adelaide, worked with ANA, and TAA respectively, as air hostesses; and then after various positions in South Australia both married and settled in Adelaide. Rosemarie finished her secondary education in Adelaide, trained as a kindergarten teacher, obtained her Bachelor of Arts (Hons), and at the time of her death had been managing a computer system while teaching at a secondary school in Canberra. She left behind her husband and two children.

In the mid 1950s, Ivy lowered her age by ten years and obtained a clerical position at Chrysler Australia and later joined the South Australian education department as a primary teacher at Brighton, where she taught for about two years.

Horace retired from the CBA in January 1959 with regret because he had wanted to complete a full fifty years’ service which would have required another three months’ work, an extension to which head office would not agree. During his retirement, Horace visited David who worked for the Australian administration it Papua New Guinea. On his second visit, when David was district commissioner based at Mount Hagen, Horace ruptured an aortic aneurysm from which he died on 21-6-1969. He was buried at Port Moresby.

Neville was the first to leave home at Queenstown (1946) to work as an assayer at a scheelite mine on King Island. He then worked his way around Australia to settle in Perth where he did extensive postgraduate studies in biological sciences which he furthered at London, Ontario in biochemistry to obtain his M.Sc. Neville now lives at Wollongong, NSW.

Paul left Queenstown in 1948 to work on the commercial and general management side of engineering enterprises in Melbourne, in Brisbane 1970-76, and in the Pacific & Far East (based in Melbourne) 1977-86. From 1987-99 Paul ran his own engineering business located at Braeside, Victoria.

Marcus worked as a civil engineer in Melbourne on major construction contracts, In the mid 1960s moved back to Adelaide, eventually joining the South Australian Public Works Department to design and supervise government contracts.

5. Letters

- Letters from the Goldfields

- Letter from Alphonse Arragon

- Letter from Charles Charreton

1) Letters from the Goldfields

[These two letters were found and transcribed by Bruno Grosse, Aix les Bains. They were translated by Rosemarie Petrasek, Canberra, 1992]

April 14, 1855

Sandhurst-Town, April 14, 1855

So it is to you my brother, gentle sister, that I address myself this time, an invalid of the gold mines who has only the use of his right hand to pen these lines. Perhaps my good doctor, you could better treat meat a distance of 600 leagues better than these ignorant practitioners of this fair country.

Since writing to Gustave on January 1st., 1855 and telling him of my long and painful sickness about which practically nothing is known, nothing has improved, on the contrary the problem has spread to other limbs and gives me no rest. I haven’t put a foot out of bed since the beginning of last February; I will detail the symptoms of this strange illness which is one of the gifts of this beautiful colony.

Since the beginning of last December, I had an irregular fever which lasted about two months, and which I treated with sulphate of quinine. This fever degenerated into sharp pains in my right knee, appearing as a swelling which prevented me from straightening and bending my leg. The joint or kneecap does not seem to be affected for I am able to move it in all directions (with my hand). The pain in the knee became almost intolerable after sunset and continued until morning. An extraordinary temperature appeared during this time which exactly resembled a high fever, without the sudden cold which usually follows a high temperature. What I felt were constant shooting pains like violent knife-thrusts in the knee particularly above and below the kneecap which by itself never seemed to be affected by the illness of the neighbouring parts.

Because the muscles and nerves are contracted my leg is now shorter than the other. When I wrote to Gustave, I told him that I had turned to quack medicine, that is to say to the ointments that cure all, but I was quickly disillusioned as I saw my pain increasing. I turned then to a German doctor recommended by miners. He treated me first of all for scurvy for six weeks after having guaranteed to cure me within this time, but I have been unable to neither leave my bed nor use my leg. I was hoping that after being treated for scurvy would mean being ready to resume work after the end of these six new weeks. But that wasn’t at all like that. Seeing the inefficiency of his treatment the same doctor began to treat me for what he called a “white swelling”. The treatment lasted more six weeks but as well as showing no improvement was poorer by 63 pounds sterling for visits and medication. I let him know my dissatisfaction with his treatment and it’s lack of success and told him that I couldn’t pay him any more, being at the end of my resources. He said would get me admitted into hospital if I wanted where I would only three guineas a week. I declined for money reasons. Fortunately I have, I suspect, in a travelling companion who has followed me for two years in our miner’s pilgrimages, a more devoted friend than you can believe. He has looked after me with all the care of a brother during this my long illness. This excellent Englishman, seeing that it was only money which was preventing me from entering hospital offered to lend me a pound of gold (50 pounds sterling) to be payed back either from my work or by my family but leaving it to my honour when that would be. I accepted with emotion and he began to organise my admission. After lots of difficulties, I finally entered the hospital two days ago. According to the doctor, I will only have complete recovery with a change of climate and cessation of the work which is the principal cause of this peculiar illness which is only apparent as a swelling and shortening of the leg and which has not let me sleep more than three nights in three months. I forgot to tell you that for five weeks my right wrist is affected with the same symptoms as the right leg and is just as painful. If I stay in hospital until the return mail, that’s to say five and a half to six months, I will have paid 72 pounds sterling as well as other necessary expenses I’m obliged to make because the food is worse than insufficient and I have had to buy bread. Fortunately my appetite has not abandoned me. I will have to pay 15 to 20 pounds in addition to the hospital fees.

My passage between here and England will cost me 65 guineas, second class. I can only travel between decks if I am better or convalescing. I can’t stay in this country where the only thing I can do is gold mining. And now the state of my health deprives me of that. If I did get better I would be exposed to the same illness on resuming that damp work underground where I would be for three quarters of the year, forgotten by my brothers and sisters who refuse to help me in not sending the necessary money to return home cured of my travels by my hard work and this painful illness? If my health had permitted I believe that I would have returned to you not exactly rich, but with a modest affluence; the 15 to 18 months of work done in fits and starts in the mines had gave me a fairly good -enough result to make me believe that 3 more years would see me with a decent income. These 10 months of illness have ruined me. Imagine that on doctor’s orders I ate a cabbage which by it’s size was only good for soup. I was obliged to pay 2 shillings(2 N 50) for it and the same goes for other vegetables. One bottle of wine is 10 shillings (12 N 50) one leech on order (2 shillings). My first doctor placed 25 leeches on me which cost me 50 shillings or 62 N 50 and on several other occasions 10 or 12 at the same price.

I have decided that if I regain my health and country, to surrender myself to the life of a peasant. It’s the only one that would please me now that I am used to hard work. I could live close to you, close to my friends, perhaps in a position of farmer or confidential agent for a farm and certainly I would make as much or more money than I do at present and it would be less painful than here where I am lodged under a tent of cotton in all weather.

The amount I ask for will seem enormous (150 pounds sterling) -3750 Napoleons, but in this country a pound sterling is less than 2 Napoleons 50 in France. So you decide that it is not possible to withdraw the money from the little I have left in France, it will be impossible for me to see you again because I must repay my debts especially to my workmate. As to the passage I cannot reduce the price without passing 80 days between decks of the boat which would be unhygienic with an illness like mine.

COST:

Passage: 65 guineas or 68 pounds 5 shillings, Present debt:50 pounds, Additional Hospital Fees:40 pounds, Total 158 pounds

30 April, 1855

(the letter continues)

No doubt you will find my letter fragmented and without style, this is because it was begun twenty times in fifteen days and I am now finishing it in hospital, on my bed where I’ve been for a week! I haven’t yet put a foot to the floor yet, however I’m experiencing a slight improvement thanks to an enormous compress placed on my knee but I don’t suppose for an instant that that will be sufficient. The doctor said that I’ll have to wait a while before he can apply heat to the leg like they do to horses in France; I don’t know whether that will effect a complete recovery! I fear that I’ll spend 4 or 5 months more in my bed, in this the dirtiest hospital ever kept by civilised people. What surprises me most is that with such a severe inflammation in my knee, my appetite hasn’t abandoned me at all, only my limbs are skeletal; the muscles themselves have disappeared, but my face hasn’t changed at all. To finalise about the money. The safest way is to make out a draft for me on the Bank of London payable at the Bank of Victoria(Australia) which corresponds with that in London and the said State Bank of Victoria has a branch in Melbourne, capital of the state of Victoria (Australia). Don’t forget to specify the state, Australia has three.

Would you write me a long letter full of events and details about my excellent aunt to whom I would have written if I didn’t know how painful it is for her write back. And my poor sick sister, my good Octavie who like me six thousand leagues away cannot leave her sick-bed. Did the sea baths restore her health? Does she walk? I’d love to hear about her. And your children: Clemence who is now a big girl, Louis who must be at school and Marie, how are they all? And you, my good dear doctor, so good, so devoted to us all, are you still a man of property. (something which I should been if I had been wiser) instead of treating your advice as useless repetitions.

My young sister Clementine, how is she? What is she doing, is she feeling stronger? Does she still have her childlike nature? Your brothers Dominique and Francois are they and their young families well? And our Grenoble cousins do you have any news of them? I wrote to Gustave on the 1st. of January. Did he receive my letter? I took the precaution of registering it as I’ll do with yours so that it gets there more quickly. Do Gustave and his family enjoy perfect health? Do they have an heir or is pretty Valentine still an only child? Is Emile’s new career prospering? Is he by chance married? The excellent (Pigeron?) family which were always so good to me how are they? Please remember me to them all. And Pergou who was such a good friend and adviser to me, if I had listened to him, what is he doing? Is his family all well? In giving him my regards listen to what he says I should do for only he has the key. I would have written to him if I could do it more easily but I trust he hasn’t forgotten me and won’t be angry about my silence.

I await a long letter with answers to all my questions about your feelings which I trust are still the same towards me in spite of my long silence.

Goodbye my dear brother, beloved sister, I will finish my letter so that I can put iodine on my knee which is hurting me. I send you warmest affection from a brother who never forgets you for a minute and has only kept silent in the hope that in a few months I would bring you news of my good fortune acquired this time through hard work. However Providence has decided otherwise! Once again, I embrace you with all my heart and wish you better luck than mine, which you well deserve.

Your brother

Edouard Permezel

My address: Ed Permezel, Gold digger, General Post Office, MELBOURNE Province of Victoria, Australia.

P.S. They call a Public Hospital a hospital where anyone can go for a charge of three guineas a week. The only advantage of that medication is included for which you would pay extra if you were treated at home and anyway is a bit more healthy than being in a tent, even though the hospital is only a wooden hut covered with canvas.

15th November 1860

Melbourne, 15th November, 1860

Edouard Permezel is writing to his brother-in-law, Dr Anthelme Chevalier:

Although you didn’t reply to the letter I sent you from England before leaving Europe for many years(this time it for ever) and that your lengthy silence since then indicates that you and your children have little wish to keep up family ties with me, I believe in spite of this it is my duty to force back my personal feelings caused by your silence to let you know that next December 1st. I will marry Miss Claudia Evans, daughter of the late Archdeacon of London (Anglican Church) and sister of Mr George S. Evans, former Minister of Public Works and member of the Australian Legislative Assembly.

I hope that the years of devoted affection I look forward to will replace the affection of those which have proved false, for which however, I will preserve all the affectionate memories of my youth, not ever forgetting the admirable sister and who still has my love. Please be good enough to tell the rest of the family about my plans. I have often discussed the qualities and affection of my excellent sister with my wife to be and in spite of differences in religion she feels a lively affection for those who are dear to me. She asks me to send you her warmest wishes. Goodbye, my dear Anthelme, my tender love to your children and believe my wish for your prosperity, I embrace you and the children,

Your former brother,

Edouard Permezel

37 Flinders Lane East, Melbourne, Australia

2) Letters from Alphonse Arragon

[Translated by Rosemarie Petrasek, Canberra, 1991]

Pont de Beauvoisin

I’m not angry with you Edouard, I even thank you for the advice that you give me because it’s always best to look for the intention and yours, I don’t doubt, is good. But, my friend, how you have hurt me: destroying without pity all the illusions of my unhappy heart. I suffered on reading your letter my dear Edouard and in spite of myself my mind retreats before the evidence that you put before me of dismissing as wrong the strong and the weak of our poor human species. To be happy in this world you have to become egotistical and hypocritical in order to escape the ridicule of men and because one must meet on the way some good and generous feelings, doesn’t it follow therefore that one must force back deep within oneself those feelings which God wanted us to have? I don’t want happiness at that price, it would be paying too dearly; I would rather suffer all my life if it means dreading the implications of our friendship. That would be the worst deception. Who knows? If it is written!… then to console myself I would say that must be so.’ According to you, to be happy I must break with a single blow all the sensitive fibres which are in me. What does the opinion of the majority matter to me if I have the esteem and approval of somebody good? Must one deny being oneself for that one thing which doesn’t resemble the masses? Come now, Edouard, my good friend, you don’t think that. And must I, as you say, in remaining what I am, a ‘loving exaggeration” incur the wrath of my mother and become the plaything of another? I would face anything rather than lie about my feelings — in so far as a sensitive man cannot stray from the path. If only I had the chance to show you how loved and appreciated you would be by a nature just like your own. Come once more to my home I would consider myself happy and would not ask for more.

I wrote several pages to you the day before yesterday the contents of which I only recall imperfectly but they would no doubt appear to you as a new French exaggeration, if they are in fact the faithful echo of my thoughts at the moment that I wrote. Excuse me once more. And since it is absolutely necessary to be up to date with one’s century if one doesn’t want to appear ridiculous even in the eyes of one’s best friend, I’ll try to be more prudent in future. You will be happy now, Edouard, your lessons and advice will have produced their effect and you must be proud to think that your affection for me has seared my heart and morally aged me. In a few days you have destroyed all the hope and illusion that my isolated existence has preserved within me. I’m going to stop now, my heart is too heavy to continue and besides I sense that my words are taking on a bitterness that I don’t want to give them. If you can understand how certain passages of your letter have hurt me, you would understand and explain all that I am trying to say but you will never know. You are too English for me. However, Edouard goodbye, I love you and will always love you and in spite of everything with the most tender and sincere affection.

Your Alphonse [Arragon]

PS My mother is in Paris. Go and see her, my friend. Make once more this sacrifice to my affection. She has a little parcel to give you and you can get from her. Goodbye again, wicked philosopher, you who calculates with his heart as I with my pen.

3) Letter from Charles Charreton

[Translated by Rosemarie Petrasek(née Permezel), Canberra, 1991]

Paris, 14 October 1859

My dear Edouard

How happy we all were when Gustave and Louise received your letters and we learnt of your safe voyage. While Louise and Valentine were away holidaying in Grenoble – they only got back a few days ago. Gustave and I often spoke of you and regretted the necessity which made you go so far away from us. How often we have followed your itinerary and tried to guess just where your boat would be. Your brother couldn’t believe that you could make the journey in less than 90 – 100 days. As for me, I remembered that this boat had already done the trip to Australia in 75 days, so I thought you would not take much longer. I wanted so much that your crossing was good that in the end I persuaded myself that it was so.

What happiness at your arrival in Melbourne! You were able to meet your friend the English doctor and others that you knew from your previous voyage. You will find yourself less alone and their connections will no doubt help you in setting up your house.

Gustave has great confidence in the success of the venture; it isn’t that he doesn’t recognise perfectly the huge difficulties you will have to surmount and the perseverance and courage you will have to display to overcome these obstacles, but he has great confidence in you and remembers the many times you have achieved your goal when he has given up.

Things haven’t been good in Europe since you left; great battles, great victories, Italian princes overthrown, a Pope who totters around on his cane chair, wonderful speeches, triumphant entrances, crowns, wounds, blood and cries for joy – we’ve had it all -and even something that we haven’t had for close on half a century in France, we’ve had a defeat. The Chinese have beaten us on the banks of the Pehi-ho, you would have probably heard of that before us. One of my relatives, a young man whom you probably met in Paris, a lieutenant with the infantry who was garrisoned at Vincennes received a bullet below the shoulder at Marigan. His arm is lost; but it has earned him the grade of captain.

So now you are up to date with what’s happened since your departure but all the papers will have arrived in Melbourne before this letter and you will be able to make some sense of all this chaos. Now putting aside these great events of a too general interest to touch us deeply when we have only a few minutes to chat together. I’m going to, without modesty, speak to you about myself and those around me, knowing the affection you have for your family – which is also my family.

Since your departure Gustave has been well, he seems to be getting fatter and his health is much better. He is still lively, but gets depressed because of all the little minor irritations of life which for him become veritable torments.

My mother, in Paris with Louise and Valentine, is today installed in the charming apartment that you discovered and waiting the arrival from Lecir(?) of my sister Adeline and my father to join them. My mother is delighted with her accommodation and is very happy to have a room which can make her forget the one she had in Grenoble. She is grateful to you for your efforts.

Since you left I have passed my exams and have succeeded in being admitted with one white and two reds – I didn’t dare hope for such a result! I have left the practice in Grenor St. Lazare Street and have joined Mr Roquebert, No. 79 St. Anne Street, a long way from Gustave’s place. I now earn about 1990 francs a year which is an enormous amount for me, having earned nothing before. But I pay dearly for this small benefit. I have to be at work at 8 in the morning and don’t leave until 11 at night. I scarcely have any time to myself. As well I sleep at the office. As you can imagine this doesn’t please Emily very much; she has cried a lot because of all these changes but understands that they’re for the best. I have kept my lodgings, new quarters that you haven’t seen which are at No.9 rue de Crevise at the corner of rue Mont Lyon. It is small as the other but it costs 450 francs instead of 300 which I can scarcely manage. Each day I spend an hour with Emily and I lose myself two or three times a week at her place. She remembers you fondly and often speaks of Monsieur Edouard. She is sorry that you are no longer in Paris. She wanted to add some words to my letter to you but this time I am being hurried on by the courier. This letter must get to Gustave’s by this evening so that it can be sent by his courier. Between here and there I won’t see Emily; she’s going to be terribly annoyed with me but next time I’ll arrange for her to write you several lines.

I’ll finish there my dear Edouard and promise to write to you from time to time. I know your heart too well now to go for long without being in touch.I clasp your hand with all my heart

Charreton

PS Emile sprained his ankle while hunting with Madame de Marcieu but it’s nothing. I believe he is alright. Your cousin Albert Gayme is very sick and we may lose him Valentine is as always the charming little girl you knew. She’s very well and has returned blooming from Grenoble. I must ask goodbye now.

I look forward to your letter.

PPS Monsieur Fevrier whom you know is Chief of the Zouare Battalion and Officer of the Legion of Honour.

Acknowledgements

The source of information on the early members of the family is the Recueil Généalogique de la Bourgeoisie Ancienne, published in Paris in 1955.

Jacques (1911) provided additional information and corrections to the Recueil, and also details of the present members of the family in France.

Bruno Grosse (1930) provided valuable information about the descendants of Jacques (1790) who remained in France.

Lionel Vallin (1955 has provided information on the descendants of Elisabeth (1765).

Francois (1954) has contributed greatly to the French information.

Ian (1932 prepared, in 1966, the Permezel Family Tree of the Australian members and a subsequent revision in 1975.

Paul (1925) has supplied the chapter about Amédée and Grace.

John (1925) brought all this work together and made an enormous contribution himself.